The only reason Los Angeles got to host its first MLB All-Star Game back in 1959 was what the Chicago Tribune called the “greed of selfish, shortsighted, spoiled ballplayers.”

Well, it wasn’t completely untrue. But the full story illustrates how the economics of baseball were changing rapidly in the late 1950s, following the bold move by two of the game’s most popular franchises to the west coast.

In 1959, an unexpected exhibition contest became the first All-Star Game played in California. It had two long-range consequences – it sparked a bidding war for national TV broadcasts of the national pastime, and it planted the seeds for the most powerful union in the United States.

This year, the Dodgers host the 2022 All-Star Game, the third time the franchise has lent its home ballpark to the contest, and the second time at Dodger Stadium. It’s been more than four decades since Los Angeles has hosted the most enjoyable of professional sports All-Star games, and more than 60 years since LA was the site of an exhibition game that a lot of people felt was unnecessary.

CA VOTER GUIDE: What are the California Sports Betting Initiatives?

Why Were There Two MLB All-Star Games in 1959?

In 1959, for the first time, MLB hosted two All-Star Games. Why?

It came down to money. The players had finally pushed hard enough to get the leagues to agree to a second mid-season exhibition to add money to an important cause: the players pension fund. However, that decision was met with disdain by many in media, which was firmly ensconced in the “management” camp at that time in history.

“Baseball players don’t need another All-Star Game to sweeten their already sugary pension pot,” wrote Jimmy Powers of the New York Daily News. A Los Angeles paper called the game “a greedy grab.”

Players Negotiated for the Game

Thanks to the leadership of pitcher Robin Roberts, infielder Eddie Yost, and soon-to-be batting champion Harvey Kuenn, the trio who represented the players in negotiations, the league agreed to add the game in Los Angeles. That decision was made only on July 8, less than a month before the scheduled Aug. 3 date for the second ASG.

Sixty percent of the proceeds from the LA game would go to the player pension fund, which Roberts explained would largely be used to pay money to “old-time” players who were in the league before 1947, had no retirement benefits, and were in dire need. At the time, former MLB players who qualified for pension funds could begin collecting at the age of 50. The league and the players had agreed to a 60/40 split of All-Star Game proceeds in 1954.

There was much controversy in the press at the time surrounding the game. Some of it stemmed from an apparent coverup by MLB Commissioner Ford C. Frick, who reportedly leaked that the 16 teams voted unanimously to support the idea. But other sources present at the time claimed that the vote was 13-1 in favor, with two teams (reportedly the Tigers and White Sox) abstaining. The no vote was rumored to have been from Cleveland.

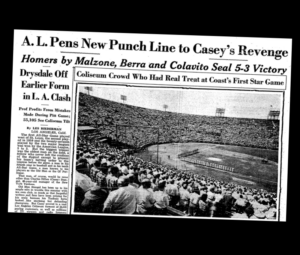

The Los Angeles Coliseum was strategically selected due to its capacity (more than 90,000 seats), which was felt could attract a giant crowd. Indeed, it did: 55,105 attended the 1959 game in LA, about 16,000 more than were on hand in Pittsburgh for the first game.

AMONG THE GREATEST: Where Does LA Ace Clayton Kershaw Rank All-Time?

1959 ASG was Must-See Event

Vin Scully, who retired from his seat behind the microphone in 2016, was on hand at Los Angeles Coliseum for the first Midsummer Classic hosted by Los Angeles. The baritone redhead was only 31 years old.

“I can remember that the team [the Dodgers] didn’t know if they would sell any tickets for a second All-Star Game with players from teams [the American League] that fans in California had never seen,” Scully said years later.

Come out they did, and not only to see ballplayers. Fans witnessed a cavalcade of stars that evening, both on the diamond and in the stands. The spectacle brought out Hollywood’s biggest stars.

Lucille Ball, star of television’s first must-see sitcom was on hand, as was movie star Cary Grant, and the beautiful Marilyn Monroe, movie starlet and former wife of Yankee legend Joe DiMaggio.

AL Gets Its Revenge

The game itself was memorable enough, though far from the most thrilling in history.

Dodgers ace Don Drysdale started the game. The pitcher had been named the outstanding player of the previous All-Star Game in Pittsburgh, played one month earlier. But on this evening the tall, handsome right-hander was the victim of two home runs – one by Frank Malzone of the Red Sox, the other by that impish quotable catcher of the Yankees, Yogi Berra.

The National League stars got homers from Frank Robinson and Junior Gilliam of the Dodgers, but the big blow of the game was a gigantic blast off the bat of Cleveland’s Rocky Colavito’s, whose homer traveled an estimated 430 feet.

The American League avenged a loss in the July game, winning 5-3 in a game beamed across the US in prime time for the first time.

Highlights and Hall of Famers

Mays made a catch reminiscent of his back-to-the-infield grab in the 1954 World Series, when the Giants star ran deep into center at cavernous LA Coliseum to catch a ball hit by Malzone. The play elicited a rare event – cheers from Dodger fans in appreciation of a Giants ballplayer.

20-year-old Jerry Walker of the Orioles started for the AL squad, and he was so unexpected in that role that even some in the press box had to scramble to learn about the fairly unknown All-Star pitcher. Walker didn’t have much time to fret over facing Aaron, Mays, Musial, and company.

“I was so scared before I started to pitch, that I didn’t have time to think about it,” Walker told reporters.

Somehow no one thought to arrange a ceremonial first pitch for the 1959 MLB All-Star Game in Los Angeles, though it was played near Hollywood, where glitz and ceremony are rarely absent. Still, the occasion was electric. For the first time, the league scheduled the Midsummer Classic to start in the later afternoon, which meant an 8 p.m. start on TV for viewers in the Midwest and East Coast.

Twenty future Hall of Famers were on the rosters. The superstars included Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, Stan Musial, and Henry Aaron, as well as Robinson and Minnie Miñoso, two pioneers for black and Latin players.

Fourteen players who were on the rosters for the 1959 All-Star Game in LA are still living: pitchers Roy Face, Jerry Walker, Bud Daley, Camilo Pascual, and Pedro Ramos; infielders Bobby Richardson, Luis Aparicio, Tony Kubek, Bill White, Dick Groat, Bill Mazeroski, and Orlando Cepeda; and outfielders Rocky Colavito and Mays.

Berra, an Italian-American born St. Louis, didn’t miss the chance to mention the contributions by himself, Malzone, and Colavito: “It’s a great day for Italians,” Yogi said.

CALIFORNIA BASEBALL HISTORY: The DiMaggio Brothers Made Their Starts in San Francisco

Second ASG More Profitable

The second All-Star Game, which would also be played each year from 1960 to 1962, proved popular and profitable. The league sold the television and radio broadcast rights in 1959 for $250,000, the same sum as they fetched for the other “original” All-Star Game in Pittsburgh.

The game in LA netted $262,336.64 in net receipts, while the earlier Pittsburgh game came in at just over $194,000.

Playing baseball on the west coast was still very unusual for teams in the American League. So much so that the Chicago White Sox, embroiled in a pennant race, insured their four All-Stars (Luis Aparicio, Nellie Fox, Sherm Lollar, and Early Wynn) for $1 million each for their safe flight to LA. They even convinced AL president Joe Cronin to have the league pay for the policy.

Dollars Continue to Rise

Within a few years of the pension wars, the players were working to form a union, and in 1965, they hired a labor attorney named Marvin Miller. The decision changed baseball history.

Within a decade, the average salary for an MLB player increased from less than $15,000 in the mid-1960s to more than $100,000 in the mid-1970s.

The league learned something from the 1959 All-Star Game in The City of Angels – primetime baseball could garner big ratings and lots of dollars.

In 1958, MLB’s sixteen teams combined to get less than $45 million in broadcast rights. But 1967, MLB was getting almost $190 million in rights to broadcast local games on TV and radio, as well as national games on two networks, CBS and NBC. The Dodgers, who became the first franchise to top three million in attendance, led the way.

AP Photo